04-02-09_02 Let Slip The Dogs Of War!

…………………………………………………………………………………….

I love my country. Anyone who knows me knows that I love America. Because I love my country, I try to keep myself educated about it’s present, future and past. You, too? Yes? Good. Then the novelty, rarity and significance of this historical tidbit will not be cast as pearls before swine. Or dogs.

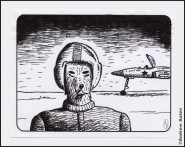

Following World War Two, the U.S. Army Air Corps and the Department of The U.S. Navy discovered that dogs – especially half-German Shepherd, half Irish Setter - make great miltary pilots.

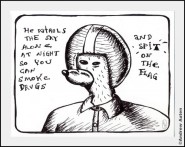

Whether it be a crude refueling station carved out of the unforgiving bug-infested jungle of a South Pacific hell-spot or the relatively pastoral and genteel environment of a Spitfire interceptor base set incongruously in the rolling English countryside, one could always count on the reassuring, homey presence of a dog. These beloved “base-dogs” served as mascots, drinking buddies, comforters, confessors and, I’m sorry to say, lovers – the latter role confined primarily to Japanese carrier ships where anything goes except homosexuality.

On these bases and carrier ships dogs clearly favored pilots over crew or ground personnel, always finding some reason to end up in the cockpit or, at the very least, the navigator’s station. At the time, most thought this was owed to the overt Alpha-male status that all pilots enjoy, a status-ranking that suits the eons-old pack mentality that governs canines both wild and domestic. There is no doubt some truth to this because a dog is ruled by his nature, as are we all and the dog more so, but ultimately the dogs stuck close to the pilots so they could observe first-hand the technique and skills required to fly an airplane.

By keeping these designs to themselves, in spite of the obvious violation of regulations, dogs were included in flights and missions with greater frequency and in greater numbers as the war progressed. Ar first, it was probably just a puppy tucked jauntily in the folds of a side-gunner’s flight thermals. Then, a dog might have been allowed to sleep in the bombardier’s perch. By the end of the war in Europe, some long-range bombing runs over Germany had crews that were outnumbered by the dogs on board. One B-17 headed for a ball-bearing factory in Bremen had at least two dogs for every crew member. That’s over twenty dogs. By the time the B-29 was introduced to the Pacific theater, some flights would leave bomb or two behind just to make room for the dogs.

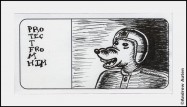

Throughout the war there were always tales, lore and hearsay about a flight that returned from a particularly hairy mission with a dead or unconscious pilot slumped over the yoke of his blood and glass-spattered cockpit. We now know it was not iron will or dumb luck at the controls of these miracle flights but dogs hell-bent on getting crew and material safely back to friendly ground.

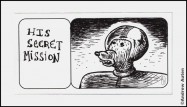

The first documented evidence of dog-flight took place at the fabled 509th Bomb Group in Roswell, New Mexico, a place perhaps best known as the setting for the infamous UFO incident in 1947. But before those events cast their spooky shadows over the somber desert-blasted tarmacs and Quanset-huts, another piece of history was quietly shat from fate’s anus. On July 10th, 1946, the 509th’s base mascot, Captain Deedles, a Schnauzer of British lineage, for reasons that are still unclear, took it upon himself to fly an unarmed P-48 Thunderbolt from Roswell to the Vance Air Base in Enid, Oklahoma. The base commander remarked at the time, “That was the best damn piloting I ever did see!”

In 1946 the Cold War was in it’s infancy. Still, the mighty U.S. military sought any and all advantage over the growing Red Menace of the Soviet Union. So, immediately after the Captain Deedles incident military researchers began covertly testing all manner of animals to see if they, too, were capable of, or even interested in, flying. Alas, no other species of animal proved to be as capable as the dog when it came to aviation. Monkeys and other primates seemed an obvious choice because the existing flight uniforms were easily modified to fit the simian build, but little else about the task seemed to suit the monkey. The sounds of the engines scared them and they could not be persuaded to keep their shoes on. Birds, paradoxical to their flying nature, proved to be unsuited to powered flight as the birds would, more often than not, wiggle out of their little harnesses and flit about the cabin, crashing into the windows until they were either dead or unconscious. Turtles were even worse as were gerbils and lizards.

The only non-dog to show any propensity for flying was a short-haired Calico cat from Wright-Patterson AFB in Ohio, who flew a helicopter for nearly ten minutes before he inexplicably decided to take a nap in mid-air. Thus, the Hiller S-55 cartwheeled into a sandtrap on the 8th hole of the Dayton Country Club.

Dogs have proven to be excellent for long-range patrols, strategic bombing and reconnaissance. Air-to-air combat is where they excel, of course, thus the term “dogfight.” In these capacities they have been an invaluable but not well-known asset to the ceaseless efforts to defend our democracy, our way of life. And all they ask in return to be told, “Good boy. You’re a very good boy.”

And good boy it is, for female dogs have shown almost no interest in flying save for “Canicula quia voro feles” or, literally translated, “The Bitch That Eats Pussy.” Lesbian dogs, in familiar English. Other efforts were made to include female dogs in the ongoing adventure of flight. The most notable and embarrassingly sexist effort was an attempt by the fledgling TWA to train bitches to be flight attendants or stewardesses, as they were called back then.

See more of Man’s Best Friend at the Artmound.

Text and Images © Andrew Auten – All Rights Reserved