My landlord of nine years, Roy Hunter, lived in the apartment below ours in a two-story duplex in Houston, Texas.

Roy was rotten, bitter and quite unpleasant. A classic woman-hater from the 50’s.  He peed into a plastic milk jug and spent his entire days just lying semi-to-entirely naked on a hospital-style bed he had wheeled into his living room. On hot days the smell of unflushed urine and uneaten chili dogs would seep in to our living room and I would have to go down to his apartment and put a cap on the piss jug and unleash some Lysol.  Sometimes I shaved him, sometimes I fed him, sometimes I started his unused and neglected car and would gun the engine for him so he could hear it run and sometimes I called the ambulance in the middle of the night when he had seizures from overdosing or mixing his meds. I would sop up the pee out of his carpet and dispose of the mattress.  And then I would visit him in the hospital.  Just me. And Rosa.

Rosa is a nearly-illiterate girl from rural Mexico who made sandwiches at Kroger. She used to. She doesn’t do that anymore.

When Roy still ventured out into the world, he would hang out at the Kroger with other ragged old men day after day. You’ve seen them, I know: gimme caps with embroidered with the names of battleships, gray velcro sneakers purchased from Parade magazine and full-body polyester utility suits or frayed golf outfits. Over the years, the men of Kroger died off or perhaps decided they could not stand the sight of so much regret and decay and retreated to apartments or hospitals. Because of her job, which she really needed, Rosa, on the other had, kept coming back to the Kroger. I was not a witness but for some damn reason, Rosa and Roy grew to like each other, certainly as much as Roy could like anyone, which wasn’t much. I think Roy knew that it was unlikely that another person would come along again. Not at this point.

Roy helped Rosa as much as his meager savings and income would allow. He bought her a wheezy used car so she could run errands for him, English lesson CDs so she could get ahead in America, and bus tickets back to Mexico so she could visit sick and dying relatives. He bought her a computer which I set up and showed her how to use. “I don’t know what the hell she’s going to do with a computer, ” Roy told me once, “Mexicans really don’t have higher brain function. Like your negroes.” Roy did love Rosa, I think. Rosa did love Roy, I think. I’m pretty damn sure. Love (and I think it was) or not, Rosa washed Roy’s clothes, cleaned his apartment, emptied his piss jug, bought his food and did whatever the hell hell else he asked of her.  Roy covered her rent on a tiny garage apartment a few blocks away and he always gave her ten bucks for a five-dollar errand, expecting she would keep the difference which she rarely did.

As arrangements went, it worked out because the circle around Roy had grown pretty small over the years and his reach to the outside diminished.  Roy had an ex-wife he called “Rags.” They divorced sometime in the 70’s. They didn’t communicate except by letter because, as Roy put it, “Face-to-face all we can do is fight.” I guess so, because 12 years of marraige and fighting didn’t yield any children for Roy and Rags. After Rags had a stroke, the letters stopped.   Once she called but her stroke-jiggered voice just sounded like an old warped LP record. He had an old drinking buddy named Earl that would drop by every now and then. I met Earl and he looked like a giant, drunk baby that could puch your lights out, even in his seventies. With his better years (if he ever had them) well behind, Earl’s ability to drink exceeded his capacity for drink and he died in a trailer home parked on his son’s hunting lease.

Roy did have a surviving cousin, but he never visited and Roy spoke poorly of him, as he did of most people. The cousin, a Walter Truitt, was a part-time evangelical preacher, part-time building contractor and full-time scumbag. Walter had a habit of not finishing the houses he started and was always kicked out of any church he started.  Once or twice a year Walter would call or send letters to Roy to share the general bland news of distant or unrelated family: graduations, deaths, births, divorces, imprisonments and paroles. I often read the letters to Roy and they seemed forced, insincere and awkward. Woven in to these calls or letters were vauge references to financial hardships the Truitt family were enduring. There was always some pressing thing such as lawyer fees, truck repairs, leaky roofs.  It was clear that Walter thought Roy was secretly rich and that his impoverished lifestyle was due to an eccentric frugality rather than actual poverty. As far as I know, Roy never gave Walter any money. Roy had always planned to leave Walter a little bit of family land that Roy inherited and that was a far as Roy would open his wallet to Walter Truitt.

A sedentary life, both physically and mentally definitely chipped away at Roy. Every now and then when I visited him, he would forget that I was present and start talking to himself, reliving old conversations. If I was lucky, it would segue into a story about his booze-powered time as an Air Force officer in Egypt during WWII (hint: he banged a lot of prostitutes) but usually his inaudible inner dialogues would turn into vicious verbal duals with adversaries long-gone.  He would forget to eat or drink. But what really did him in was an overdose of some med or another that paralyzed him temporarily. For about two days he lay in his bed on an ever-increasing puddle of filth until the paralysis finally eased and he was able to call me. When I got to him, he was as scared as I’ve ever seen a human being. Except maybe for Rosa. She left her shift at Kroger as soon as I called her to be at Roy’s side. Her grief was utterly boundless as she would never forgive herself for leaving Roy alone for a day.

Roy did not have a stroke or heart attack, although his loopy behavior would lead the doctors to initially consider this. He did have a mild kidney infection.  Every med they tried just made Roy hallucinate.   At one point he thought all the nurses were naked angels sent by God to blow him for all eternity.  Declared neither sick nor cured, Roy was moved to a nursing home which was such a horror show I figured Roy was better off dying in his own shit and so did Roy. We convinced the insurance company to stop paying the nursing home bills, and shortly after that the nursing home announced Roy was rehabilitated and able to care for himself after all.

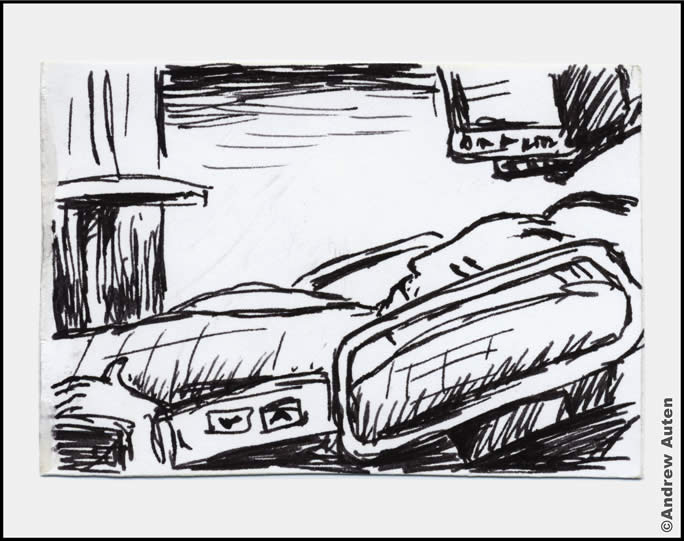

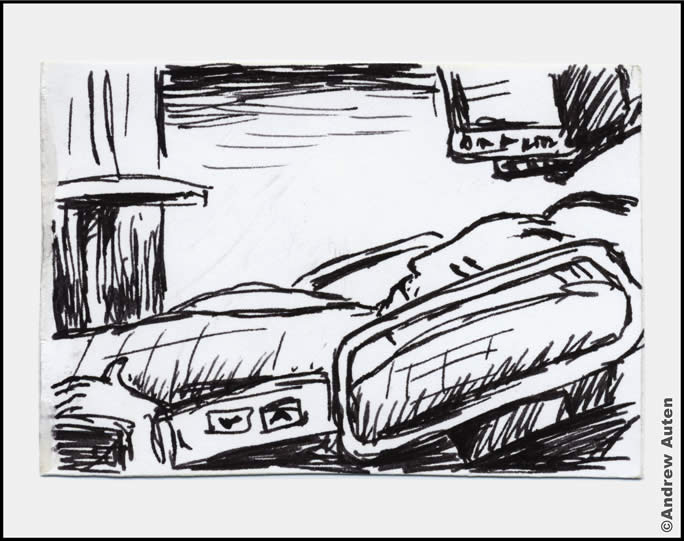

A rented ambulance moved Roy back to the bed in his living room where he just stared out the window for weeks at a time. But every single fucking day Rosa came to visit bringing food, cranberry juice or very often just the sound of her voice.

It was obvious to anyone who had any contact with Roy that he was on his way out. Formerly full of piss and vinegar, however artlessly executed and poorly applied, Roy was now merely full of piss. And that’s when Walter Truitt decided it was time to leave Allen, Texas to visit his long-lost cousin in Houston. Roy was actually glad to see the one remaining fragment of blood-family and he called me down to his apartment to meet Walter and his wife.

Walter Truitt. Late 60’s. Conway Twitty pompadour.  Creased cowboy pants. Cartoon devil beard. Gold cross on a chain resting conspicuously, accusingly on an exposed mat of grey chest hair. A dog-eared bible bulging with post-it note bookmarks in his tanned, pinky-ringed hand.  His wife was a never-pretty lump with an a mean, hard face topped buy the uttery standard cauliflower helmet of hyper-permed, tinted hair that has become, inexplicably, the only hairstyle available to women over 50 in America. The two sat near Roy’s bed in a manner I’ve seen before when my cat has a legless grasshopper corned in the kitchen.

Our first conversation:

Me:Â It’s good to meet you at last.

Walter: How come you’re not at work?

Me: I am. I work at home. I’m a designer.

Walter: Aw, you need you to come up to the country and work construction on my new church.

Me: I can’t. Homosexuals make me nervous.

Hey – he was never going to like me, okay? I don’t remember the rest of the conversation except that Jesus was mentioned quite a bit and guns were worked in a few times, too.

The visits from the Truitt family became more frequent. With each visit, Walter talked Roy out of more of his posessions: guns, coins, tools, fishing poles, furniture and finally, cash money. I paid Roy’s bills and sometimes helped with his taxes so I really did know how much money he had. Roy had about 30 grand to his name but he owned the duplex we lived in and one other rental house. The rent covered the taxes with a little left over for repairs and living expenses and Rosa’s rent. As the weeks and months passed, Walter worked on Roy’s softening mind, convincing him at one point to sell the other rental house to an appraiser Walter knew who insisted the house, in a prime thriving neighborhood, was worthless. Shortly after that Walter was driving a new pickup truck.

I was out of town when Roy collapsed for the last time.

My next-door neighbor, Mary, called me to say that an ambulance had taken Roy to the hospital a few days ago and now there was a man and woman tossing Roy’s apartment. She could see through the window that they were dumping out boxes and papers. I said, “Don’t call the cops. I know who they are.” Piecing together the timeline later, I figured out later that Walter had gone to Roy’s house first to look for the will before he went to the hospital to check on Roy. Walter and his wife had spent an entire day going through what was left of Roy’s belongings.

When I got to the hospital the next day, Rosa was already there. She had been there for days. She had her hand on Roy’s head, her small hand touching his waxy skin as she prayed in Spanish and English, “Jesus please save my Popi, please Jesus, my Popi he is sick.” I am crying right now as I visit this thought.

When I got home later that night there was already a “For Sale” sign in the front yard of our duplex. Walter was waiting for me on the porch with a letter from a lawyer which he brandished at me like Father Merrin wielding a crucifix against the devil. He could barely contain himself as he proudly, breathlessly took me though the point-by-point legal babble that basically said Walter Truitt is at long last running the show and now it’s time to kick the godless faggot, his hippie wife and the Catholic wetback out of the picture.  He implied that things might go a little easier for me if I testified that Rosa had been stealing from Roy.

Me: What makes you think she’s been stealing?

Walter: Because all of his money is gone.

Me: He never had any money.

Walter: ?

Me: He’s broke. This house and the bit of family land is all he has.

I had always advised Roy to sign the house over to Rosa while he was alive or at least will it to her. Walter had convinced Roy to will the duplex to him at least two times that I know of but Roy would change the will after Walter went back to his church in Allen, Texas and future death-activated ownership would revert back to Rosa.

The next morning I went to visit Roy at the hospital. Rosa was there already. So was Walter and his wife. They stood in the corner of the ICU room, away, literally in the shadows, as we talked to Roy, urging him to come back from this mysterious land of Nod which had captured him. The doctors, as before, were utterly at a loss to explain what had happened to Roy or what was happening now. “Roy, you’ve got to come back, ” I would say to him, “Rosa needs you.” Sometimes he would answer in a sleepy voice, “I can’t.” “Come back, Roy.” “It’s too far, ” he said, “I’ll see you on the other side.” I never saw Roy again after that. Not because he died but because the Truitt’s and thier lawyers had Rosa and I banned from the hospital later on that very day.

Yeah, he did die, a few weeks later while the Truitt’s, Roy’s only living family, had gone back to Allen, Texas to put the family land up for sale. Land they hadn’t even inherited yet at that point. So Roy died alone.

The long and short of what remains of this story is that through my willingness to testify in court against the Truitt’s, Rosa did eventually inherit the house which is probably worth half a million dollars at least, these days. I have not talked to her since my court appearance. We moved out quite hastily, because although we enjoyed my nine years in that apartment, our last six months were a real misery. Besides, lawyers for boths sides were trying to get us to affirm this or that, swear to one thing or another. The whole thing was too sad, really.  Before I moved out I took the plastic Dymo label off Roy’s front door and put it in my wallet where it remains today. In crudely punched-out letters it reads “R. Hunter.”

So what is this? What happened?  The love a country bumpkin from Mexico felt for a rotten old man truimphed? That’s what the optimist would see, I’m sure. Born-again hillbillies are untrustworthy?  Maybe. You see what you’re looking for. I know that much.  Rosa saw an old man that needed her help. Roy saw his last chance at decent human contact. Walter saw what he thought was a rich old coot and conniving vultures carving up an inheritance that rightfully belonged to blood-relatives. And I saw this.

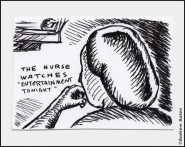

This drawing is from the last time I saw Roy.

Text and Images © Andrew Auten – All Rights Reserved